This post is part of my series on organizing “between and beyond.” Other posts are here. The purpose of this post is to explore the history and key assumptions of Sociocracy and Holacracy®. The post is based on my previous posts about Sociocracy and Holacracy. The analysis is summarized here.

Background

I first heard about Sociocracy and Holacracy in 2012. Both attracted my interest and I wrote an enthusiastic book review of We the People: Consenting to a Deeper Democracy by John Buck and Sharon Villines in November 2012. I subsequently participated in several Sociocracy workshops with James Priest, got training in facilitating Sociocracy by The Sociocracy Consulting Group, and wrote an ebook on Sociocracy (in Swedish), Sociokrati: En metod för självstyre, together with John Schinnerer.

History

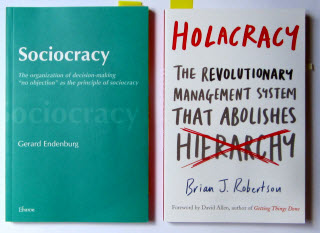

Sociocracy is a governance method based on consent decision-making and cybernetic principles, which was developed by Gerard Endenburg during the 1960s and 1970s. Endenburg published his first book on Sociocracy in 1981.1 The early development of Holacracy was influenced by sociocracy. Brian Robertson filed a patent application on Holacracy in June 2007 (Pub. No. US 2009/0006113 A1), where sociocracy, in my view, is prior art. The patent application was subsequently abandoned. The first Holacracy Constitution was launched in 2009. Robertson’s book on Holacracy was published in 2015.2

Objectives

Objectives

Gerard Endenburg’s objective with Sociocracy is to enable everyone to develop as far as possible,3 while Brian Robertson wants to harness the tremendous sensing power of the human consciousness available to our organizations.4

Assumptions

Endenburg and Robertson have very different views on organizations and their purposes. Endenburg thinks that organizations exists for the people,5 while Robertson views the organizations as separate entities that have their own purposes beyond just serving people.6 Endenburg emphasizes the importance of each person’s equivalence in the decision-making and the potential for existence and development,7 while Robertson views people as role fillers8 and differentiates between role and soul.9 Robertson’s favorite metaphor to illustrate dynamic steering and constant weaving is riding a bicycle.10 Endenburg uses the same metaphor to illustrate weaving and the circle process.11 Both use nested circles which are linked via two separate roles.12,13 In short, both use the same basic rules, or principles.

Incompatibilities

Endenburg and Robertson use very different languages. Robertson’s book is very readable, while Endenburg’s book is difficult to read. Endenburg admits that he may sound rather cold and formal, but thinks it’s necessary.? Robertson, on the other hand, uses words creatively, and gives them his own slant. He calls, for example, the organizational structure of nested circles a holarchy,14 a term coined by Arthur Koestler. Robertson also claims that Holacracy abolishes hierarchy, while a holarchy, according to Koestler, is a hierarchy.15

Sociocracy and Holacracy are based on specific assumptions applicable to mechanical and electrical systems. Endenburg uses two examples to illustrate the feedback control loop, or circle process, in cybernetics. The first example is, as already mentioned, riding a bicycle.16 The second metaphor is a central heating system.17 Endenburg acknowledges that the operating limits in riding a bicycle are different from those within a heating system, but he still thinks that they indicate constraints within which control may be exercised.18 Endenburg is aware that riding a bicycle is far more complex in reality than his simple example might suggest.19 He also acknowledges that people are not system components,20 but he doesn’t distinguish between machines and organisms in his reasoning.21 Neither does Robertson, who views people as sensors for the organization.22 But people are not machines (or sensors). Machines and organisms ARE different.

Holacracy prioritizes the systemic value of thought by keeping intrinsic human values out of the organizational space. Robert Hartman showed how values can be measured systemically, extrinsically, and intrinsically.23 For example, systemically a worker is a production unit, extrinsically one of several workers, and intrinsically a human being. In Holacracy, systemically an individual is a role and sensor, extrinsically one of several roles and sensors, and intrinsically a human being. The whole point of Holacracy is to allow an organization to better express its purpose.24 Every individual becomes a sensor for that purpose.25 Holacracy is focused on the organization and its purpose—not on people and their needs.26 The focus is only on what’s needed for the organization.27 Holacracy installs a system in which there’s no longer a need to lean on individual’s connections and relationships.28 Holacracy keeps human values out of the organizational space. 29 According to Robert Hartman, there is a tremendous gap between those who think in terms of human values and those who think in terms of non-human systems.30 Elevating systemic values OVER intrinsic human values is dehumanizing. Hartman goes a step further and says that ignoring life’s intrinsic value is the danger that threatens life itself.31

Conclusion

The operating limit on Sociocracy and Holacracy is that people are “autonomic”.32

Notes:

1 Gerard Endenburg’s first book on Sociocracy was originally published in Dutch in 1981. The first English translation was published in 1988. The Eburon edition was published in 1998. See Gerard Endenburg, Sociocracy: The organization of decision-making (Eburon, 1998).

2 Holacracy is registered in the US Patent and Trademark Office. Brian Robertson’s book on Holacracy was published in 2015. See Brian J. Robertson, Holacracy: The Revolutionary Management System that Abolishes Hierarchy (Penguin, 2015).

3 Endenburg, Sociocracy, p. 5.

4 Robertson, Holacracy, p. 7.

5 Endenburg, Sociocracy, p. 142.

6 Robertson, Holacracy, p. 148.

7 Endenburg, Sociocracy, p. 167.

8 Robertson, Holacracy, p. 92.

9 Ibid., pp. 42–46.

10 Ibid., p. 129.

11 Endenburg, Sociocracy, pp. 16–19.

12 Ibid., pp. 10–11, 26–27.

13 Robertson, Holacracy, pp. 46–56.

14 Ibid., p. 38.

15 Arthur Koestler, The Ghost in the Machine (Last Century Media, 1982, first published 1967), p. 48.

16 Endenburg, Sociocracy, pp. 16—19, 23, 33—37, 223—224.

17 Ibid., pp. 19—23, 30, 36, 40.

18 Ibid., pp. 23, 30.

19 Ibid., p. 16.

20 Ibid., p. 39.

21 Ibid..

22 Robertson, Holacracy, pp. 4, 166, 198.

23 Robert Hartman, Freedom to Live: The Robert Hartman Story, p. 67.

25 Robertson, Holacracy, p. 34.

26 Ibid., p. 166.

27 Ibid., p. 198.

28 Ibid., p. 199.

29 Ibid., p. 200.

24 Ibid., p. 202.

30 Robert Hartman, Freedom to Live: The Robert Hartman Story, p. 124.

31 Ibid..

32 There is a distinction between being “autonomic”, obeying self-law, and “allonomic”, obeying some other’s law. See Norm Hirst, Research findings to date, Autognomics Institute, (accessed 4 August 2016)

Related posts:

Organizing in between and beyond posts

Book Review: Sociocracy

Book Review: Holacracy

Book Review: Freedom to Live

Holacracy-vs-sociocracy

The phenomenology of sociocracy

Is sociocracy agile?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.